Every commentator, and every recent report, says the same thing. The UK Higher Education sector is financially unsustainable, and it is only a matter of time before something breaks.

The sense that “we cannot go on like this” is now pervasive across the sector. No one expects more funding from government – whichever party that is, and yet there seems little appetite to explore fundamental changes to the delivery of Higher Education whose model, with a few notable exceptions that just serve to prove the rule, has barely changed in generations. Undergraduates are still almost all enrolled on three-year residential programmes progressing through three levels of study to end with a bachelor’s degree and, hopefully, a decent job. This is the way it’s always been done. Although this basic delivery model might not have kept up with changing times, demand for it remains high and there is much to admire in it. It gives young people a great opportunity to leave home, broaden their horizons, have time between study commitments for work and play, and to learn their subject from experts who are often leaders in their field.

But it is clear to everyone that the basic unit of resource – the £9k annual tuition fee – will no longer support this model and things will only get worse as that figure is further eroded by inflation. The normal response to this problem is for universities to get bigger – in every sense of the word. More students, especially more international students, bigger student: staff ratios, bigger campuses, and more facilities. When the unit of resource is so squeezed it makes sense to spread the high fixed costs of running a university across as many units as possible. Granted, the immediate institutional response to financial pressure is normally to cut costs but the longer-term plan is nearly always to grow out of trouble. Restructure, agree growth plan, rinse, and repeat.

This growth then causes its own problems. The “massification” of Higher Education is simply giving the sector’s critics new ammunition to attack it. Many students find their crowded lecture theatres to be so impersonal that, far from the enriching social experience they expected, the crowd of strangers around them leaves them lonely and homesick. At an extreme end of the scale, the mental health and well-being of students is at risk in these conditions. High proportions of international students leave institutions scarily exposed to changes in immigration policy and the drive to fill universities with students on cheap to deliver courses generates headlines about “rip off” degrees which tarnish the reputation of the whole sector.

The problem with changing is that it involves so much change

I expect that most Vice-Chancellors, if asked, could imagine a completely new model of higher education delivery for their own institutions if only they did not have to confront the sheer scale and difficulty of actually implementing it. Whilst the UK University sector enjoys a reputation that has long been the envy of the world, this proud heritage also means that, as organisations, institutions are often so frozen into their legacy of structures, systems, regulations, industrial relations, and ecosystems of partnerships that they can’t fundamentally change. Making major changes to the delivery of undergraduate education is a game of management and regulatory whack-a-mole. Each planned change leading to some new unintended problem or regulatory issue.

A time machine is needed. Vice-Chancellors could then re-imagine their Institutions fundamentally and design a delivery model that works. They could then jump into the time machine, set the dial for say, five years hence, and re-emerge to a completely different institution enjoying the stability and security of a rationally designed delivery model operating in a financially secure steady state.

New HE providers could be that time machine.

They offer a glimpse of what the future could look like. They are institutions built around their delivery model and combining the best approaches from across the world into genuinely new models of degree level education. They could even hold the answer to that key question: how to deliver high quality degree level education to students in economically needed STEM courses within the unit of resource provided by the current student finance regime.

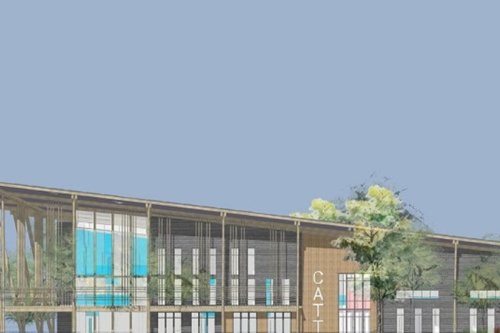

NMITE is one such new provider establishing itself in the small city of Hereford and providing degree level courses in Engineering, Technology, and the Built Environment. It is also sowing the seeds of the skills, employment and knowledge based economic regeneration that universities can so effectively drive in their regions. Our institution focuses heavily on academic quality and the student experience, but we have avoided the need to build much of the costly infrastructure that characterises large institutions. We are leaner because we are small, and we avoid many of the downsides of massification. Our students know each other, and we know them; and each one knows they matter. Our infrastructure, systems and business processes are simple and lean – and they can be changed easily since there is little resistance of the “we’ve always done it this way” type. A normal student timetable involves working on campus all day, every working day – like a job – but this means that their courses are a full year shorter than the standard model. It also means that our campus, a blend of repurposed buildings and new structures, provides only what we really need and what we intensively use. It could be described as a “no frills” university but I prefer to call it a “focus on what matters” institution.

Our simpler, smaller configuration makes institutions like NMITE much more deployable to those “cold spot” areas - towns and regions with no local university and where fewer young people go on to study for a degree - than traditional institutions who still don’t reach these left behind areas despite years of “outreach” programmes and widening participation schemes. Imagine being able to increase university capacity in the regions where it will actually make a real difference to the life chances of the local population?

Despite the expansion of new vocational pathways and qualifications which provide an important choice for many, the demand for full time university degree courses remains as high as ever. Getting a good university degree is still perceived by many parents in the same way they view home ownership, an important enabler for a life of economic security and professional fulfilment. But if the HE funding model is fundamentally broken, we must be more ambitious about developing, testing and investing in new models. It is the only way we will find the elusive solution to the funding conundrum everyone is writing about.

James Newby, President and Chief Executive

Discover the NMITE difference for yourself at nmite.ac.uk